Indeed, in the time of early cinematography promoting goods by means of posters was still in its infancy, as far as our territory concerns. Local artists were largely inspired by French posters, generally considered of high quality by specialists in the field and frequently put up in public spaces. As local businessmen active in the field of cinematography had originally little confidence in posters serving as advertisement, it was only in the 1910s that first picture film posters started to appear.

Before that, only text posters, also called “typographic” were used: these presented movies as technical innovation – “live photo” – and promoted programmes in cinemas. In addition to the text, some posters featured small ornaments, decorations or pictures. Later, poster formats were standardized to A1 and A3 formats, while early stage was typical for format inconsistency. However, most common were large formats, the length of some posters could even exceed 2 metres [1] Another popular poster was a narrow “noodle” type, common until the 1950s: these varied in length and were about 30 cm wide, being thus space- and paper-economical.

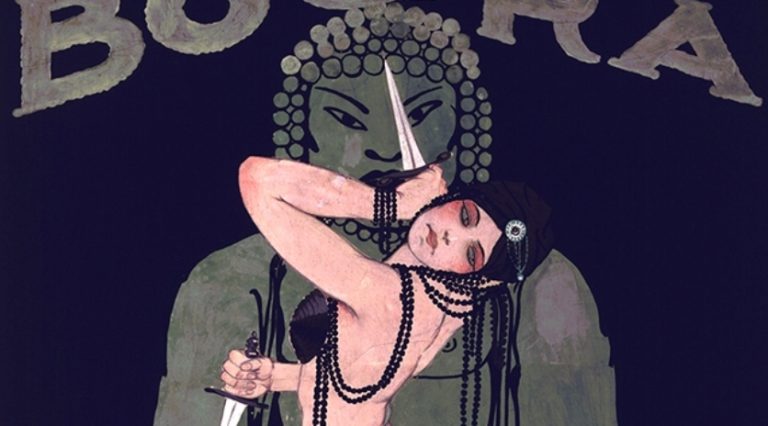

Posters’ style as well as their authors were influenced by Art Nouveau, in its final stage, as well as by just emerging modern artistic styles – art deco, national decorativism, cubism, constructivism, neoclassicism, etc. The oldest picture poster clearly featuring final stage of Art Nouveau, was designed by Josef Wenig (1885 – 1939), academic painter, in 1913 for a movie called Idyla ze staré Prahy (Old Prague Idyll, 1918) which did not survive until today. Yet it is not a sole example of a poster that survived while its movie had been lost. Other examples include posters to Šestnáctiletá (Sixteen-Year-Old, 1918) by František Xaver Naske (1884 – 1959), Tanečnice (Lady-Dancer, 1919) by Vlastimil Košvanec (1887 – 1961) or Ferdinand Fiala’s (1888 – 1953) poster to movie Bogra (1919). In such a situation poster provides documentation from the relevant period and serves as evidence of the movie, information in the text or in the picture might provide further details about it. However, we might also find examples when a movie survived while its poster had been lost.

First picture movie posters were typically made using lithography technique, very often not even featuring the movie title. Indeed, the text was rather sparse: just name and brand of the movie distributor or producer.[2] There are examples of texts written by hand, additionally printed or glued with date and place it will be screened, especially on white areas of narrow posters. At the end of the 1910s, posters started to display names of actors and, subsequently, names of major domestic directors, which justifies the fact that our market was slowly establishing the system of stars. First personalities with their names put on the poster include Suzanne Marwille (first time presumably on the poster to 1919 Bogra movie mentioned above). Other early members of the developing star system were Anny Ondráková; Vladimír Chinkulov Vladimírov, Russian emigrant; Emil Artur Longen and Karel Lamač. At the end of the 1920, posters started to feature also Vlasta Burian, biggest poster star of the 1930s. Actors and directors were soon followed with authors of famous books the movies had been based on, international personalities and then also other movie professions: indeed, the text was still expanding. Gradually, font size used for the names of personalities increased, the biggest stars were printed even in larger font than the movie title. Furthermore, posters depicted also more and more specific actors, which makes them comparable to posters as we know them today: faces and names of stars dominating with no visible artistic efforts.

In the 1930s, headlines emerge on posters, especially on those promoting international movies. The level of detail they provide ranges from mere superlatives of the type: “Comedic feature film boosting with vivacity, great, fascinating and amusing!“, that appeared on a narrow poster to Kde se pivo vaří (Where the Bier is Brewed, 1935) to those summarizing the plot: “Mystery of U 170 submarine drown loaded with gold during the World War. Exciting and nail-biting fight between diver and octopus threatening the crew on a submergible device!” on a noodle promoting Kapitánův poklad (Captain’s Treasure, 1933). Fairly often though there was too much of text on the poster.

Lithography period ended when considerably cheaper option, offset printing, was introduced. At the same time, cinematography went through another milestone, i.e. synchronous sound was introduced. As cinematography turned from silent to sound at the turn of the 1920s and 1930s, this technical innovation was duly highlighted on the posters with headlines such as “speaking and singing movie” or simply “sound movie”. While first posters presented a single picture, drawing or painting, 1930s movie posters marked significant visual change. Indeed, they became a puzzle made of drawn photographs of movie characters or scenes, with one-colour surfaces in the background instead of painted background. Gradually, slightly abstract silent-era posters inspired by various artistic styles turned into a sort of hyperrealism. Furthermore, some later Czech posters promoting international movies are clearly adopted or at least partly created based on original printed promotion from abroad. The period of Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was characterized by the same esthetics, while all posters used bilingual text, including the movie title, in Czech and in German.

Even though a wide range of important or interesting authors engaged in posters creation, many of them have remained rather unknown until today. What we know about some graphic artists is just that they were authors of some of the posters survived until today, but we do not know any further details from their personal lives. Sometimes we do not even know the artist’s name – just a part of it, acronym or pictorial symbol used as a signature on the poster. And there is a large number of posters where the author is totally unknown.

Obviously the most curious symbol, shark depicted in a number of varieties was used as a signature by Albert Jonáš (1893 – 1974), pioneer of modern Czech promotional graphics. His prominent works date back to the 1930s, painted by so called airbrush technique.[3] Though it is not widely known, even Martin Frič (1902 – 1968), film director, engaged in movie posters creation: though he designed posters for other directors’ productions, such as Švejk v ruském zajetí (Švejk Captured by the Russians, 1926) or Životem vedla je láska (Love Led Them Through Life, 1928). Most prolific and prominent poster designer in the silent era was Václav Čutta (1878 – 1934), while early sound movie and the 1940s period is represented among others by Josef Burjanek (1913 – 1992), Kožíšek (?), František Přibyl (?), František Zelenka (1904 – 1943), Miroslav Zikán (1907 – 1981) and many others. In fact, the only silent-era author that continued to be active in the 1930s was Ferdinand Fiala.

In that period, promotion ateliers with a number of professionals played a significant role. Major ateliers were owned e.g. by Josef Burjanek (Atl. Burjanek), L. A. Vodička (Vodičkova reklama, Vodička Promotion), Jiří Jelínek (Remo) or Vilém Rotter (Atl. Rotter). The latter, Vilém Rotter, owned besides the promotion atelier also public school of applied graphics, its most famous student being Karel Vaca (1919 – 1989), one of key representatives of Czechoslovak film poster golden age. Posters were printed in a number of printing companies, the most prominent being K. Kříž’s company with posters designed among others by Čutta and Fiala mentioned above; J. Zieglosser’s printing company; Melantrich; or a company in Brno called Jarkovský and Svoboda. When offset printing was introduced, companies that refused to adopt this technology went bankrupt sooner or later, such as Zieglosser printing company. At the same time smaller companies, such as Jarkovský and Svoboda company or J. Doležal from Červený Kostelec used this opportunity for their benefit. Ateliers and privately-owned printing companies engaged in movie posters until 1948, a year when polygraph industry was nationalized; movie industry was nationalized already three years earlier, in 1945.

The period of First Czechoslovak Republic marked no significant response to Czechoslovak movie poster, both at national and international scene. Film reviewers tended to stick to French movie poster, taking it for unequalled model, even though the quality of Czech movie poster increased in the 1920s. Nevertheless, Czechoslovak film distributors were of little help with their efforts to save as much as possible on promotional activities, often unwilling to hire high-quality domestic designers. Furthermore, public opposition against national film posters was also connected to broad public discussion against negative impact of cinematography on moral education of young people, etc. Objections were raised against erotic or violent motives depicted on posters and serious discussion was held concerning correct look of the posters.[4] Nevertheless, as sensational, erotic or exotic “publicly shocking” posters presumably increased cinema attendance, cinema operators would not much bother with the ethical point of their presentation.

In fact, Czechoslovak film posters went through a number of changes in the first half of the 20th century: painted lithographic posters bearing minimum text were replaced with offset-printed posters based mainly on photographs reproduced in painting. Focusing on film stars and not featuring any artistic condensation, the 1930s posters are quite comparable to advertising as we know it today. Despite distrusted by film distributors at the beginning, movie posters soon turned to be used for film advertising, serving for that purpose together with printed advertising in the media as the sole option for quite some time. Even though they had not been appreciated by artistic reviewers, posters from this period deserve credit for their unique visual quality, notable designers and especially for preparing grounds for the 1960s golden age of film posters.

Bibliography:

Kopcová, Zuzana. Albert Jonáš 1893 – 1974 (master’s thesis). Olomouc: Department of Art history, Faculty of Arts, Palacký University 2013.

Kopcová, Zuzana. Atelier Rotter 1928–1939 (bachelor’s thesis). Olomouc: Department of Art history, Faculty of Arts, Palacký University, 2007.

Malý, Pavel F. Spolupráce malířského umění s filmovou tvorbou II. Český filmový svět 1922 – 1923, v. 2, No. 3, p. 16.

O velkých plakátech biografů. Zpravodaj Zemského svazu kinematografů v Čechách 1926, v. 6, No. 8, p. 5.

Pás 1935, No. 8–9, p. 6.

Plakáty. Kinoreflex 1929, r. 19, No 3, p. 42.

Filmové listy 1931, v. 3, No. 8, p. 3.

Štembera, Petr. Český filmový plakát od počátků do prvních let druhé světové války. In: Sylvestrová, Marta (ed.). Český filmový plakát 20. století. Brno: Moravian Gallery in Brno, 2004, pp. 14–24.

Reklama pro film. Film 1929, v. 9, No. 2, p. 2.

Šúr, S. Český film – náš film (Původní dopis ze Slovenska). Filmová Praha 1923, v. 4, No. 31, pp. 242–243.

Tabery, Karel. Česká recepce filmových plakátů ve dvacátých letech. In: Sylvestrová, Marta (ed.). Český filmový plakát 20. století. Brno: Moravian Gallery in Brno, 2004, pp. 25–34.

Zelenka, František. Český filmový plakát. Studio: měsíční revue pro filmové umění 1931–1932, v. 3, No. 7, pp. 281–282.

Notes:

[1] The biggest movie poster that survived until today had been designed for Tu ten kámen (This Stone Over Here, 1923) (the movie was lost); dimensions of the poster: 175 x 234 cm, placed in the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague.

[2] S. Šúr, who lived in Slovakia, was one of those who complained about lack of information presented on the posters, having stated that the poster does not indicate even whether the movie promoted is of Czech origin, which justifies insufficient promotion of domestic work.

[3] “Airbrush technique” is spraying of colours using a spray gun, enabling transition of colour set.

[4] High-quality poster should be impressive, not too loud as regards colours, simple, without too many details, not too wordy and original in idea.