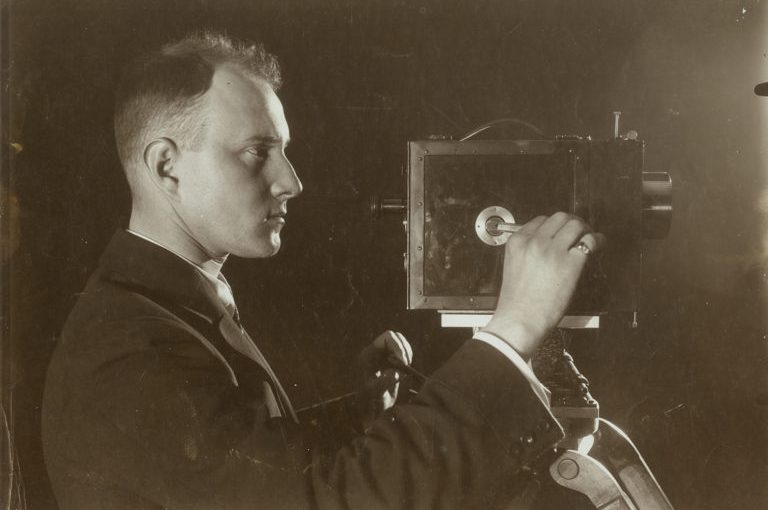

Born on 27 June 1897 in Prague, Jindřich Brichta passed his school-leaving exam at “Realgymnasium”, high school focused on mathematics and science, in 1915 and started his studies at the Czech Technical University in Prague, where he graduated in 1923 as construction engineer. Later on he attended lectures at Prague Charles University, Faculty of Science. Indeed, with his curious and strong-willed nature, he had always been attracted by technology, new inventions and progress, being interested in railways or fire workers, though his biggest passion was for cinematography. In 1917, during his studies, he met Karel Degle, young cinematographer who showed him secrets of film technology and cinematographer’s work. Indeed, it was also Mr. Degl who secured Brichta free-of-charge internship experience in Lucernafilm film production company a year later. Both of them made photographical evidence of autumn 1918 events.

Brichta then worked as cinematographer in the following companies: Bratři Deglové (The Degl Brothers, 1918–1919), Wetebfilm (1919–1921) and Comeniusfilm (1922–1924). In this period he shot just few live actions but a high number of short films, reporting and news shots. Later on he was active as producer, cinematographer, documentary and reporting film director. He engaged also in the field of science cinematography: already in 1920 he and professor Vladimír Úlehla carried out experiments in time-lapse photography and biological film. Four years later, he co-founded Czechoslovak Society for Scientific Cinematography, together with Karel Smrž and Viktorin Vojtěch, and he was also editor of the Kinematografia (Cinematography) magazine published by this society since 1926.

Besides these activities, Brichta continued extending the scope of his activities: in 1919 or 1920, he participated as cinematographer in research expedition organized by archeologist Karel V. Absolon and Brno Moravian Museum in Yugoslavia. In 1925, having received grant from the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Agriculture, he carried out a study journey to Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Great Britain and France, he studied at Marey Institute in Paris and met a wide range of artists and creators (such as Lucien Bull, Louis Lumière, Georges Sadoul), with some of them he even engaged in cooperation. His other activities include managing position in a student cinema Alma (1921–1922), technical director of film reporting in Elektajournal (1927–1931) and Aktualita (1937–1943); between 1932–1937 he had contracts to make shots for Czech as well as international weeklies (UFA, Pathé, Fox, Universal). Last but not least, he was expert witness in the field of cinematography and cinema technologies. He is also author of several technological innovations.

To come back to Brichta cinematographer, he proved to be endowed with a sense for visual esthetics of film scenes, being capable of connecting outdoor scenes with indoor, capturing them in an impressive and vivid manner. Between 1918 and 1929 he made a total of thirteen live actions, mostly feature films: the first one, O děvčicu (About a Girl, 1918) was intended as folklore drama. Directed by Josef Folprecht and Karel Degl, the film was produced just few days before independent Czechoslovakia was established. The following year, he was director of photography in Stavitel chrámu (The Cathedral Builder, 1919), trick-demanding historical drama directed by Karel Degl and Antonín Novotný. Indeed, the movie made great artistic success and was sold abroad, mainly because of pioneer trick models in scenes depicting cathedral scaffolding on fire.

Followed legionary drama Za svobodu národa (For the Nation’s Freedom, 1920) produced by director Vladimír Binovec and his Wetebfilm Company; fanciful drama Plameny života / Ráj a peklo bohémy (Flames of Life / Heaven and Hell of the Boheme, 1920) a adaptation Černí myslivci (Gamekeepers in Black, 1921). Furthermore, he participated in the first production by director Josef Rovenský with his melodrama Děti osudu (Children of Destiny, 1921). Having made a five-year break, he shortly came back to fiction cinematography, involved in the dramas as follows: Řina / Tři lásky Řiny Sezimové (Řina / The Three Loves of Řina Sezimová, 1926), by Jan S. Kolár[1]; Ve spárech upíra (In the Clutches of a Vampire, 1927) by Květoslava Semonická and Theodor Pištěk; or Pražské děti (Prague Children, 1927) by Robert Zdráhal. Last time Brichta was involved as live action cinematographer, in cooperation with Karel Kopřiva, Jan Stallich, Otta Heller and Václav Vích, was in Svatý Václav (St. Wenceslas, 1929), the first Czech epic film ever, directed by Jan S. Kolár.

As far as Brichta documentary and reporting cinematographer is concerned, he shot different kinds of events and curiosities, being author of the following titles Akademický dům v Praze (Academy House in Prague, 1919), Jak rostliny žijí a cítí (How Plants are Living and Feeling, 1920), Slovácké tance a obyčeje (Moravian Slovakia Dance and Traditions, 1922), Cesta kolem republiky (Journey around the Republic, 1923), Malebné pouti po Bosně a Hercegovině (Picturesque Wanderings in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1923), Náš Jáchymov (Our Jáchymov, 1925), II. Dělnická olympiada v Praze (The Second Worker’s Olympics in Prague, 1927), Ze života rostlinné buňky (Life of a Plant Cell, 1928) and many other. This period marks also Brichta’s directed mid-length document Demänová (1928) on cave explorations.

His work as cinematographer and director in the 1930s and 1940s include Střední Slovensko (Central Slovakia, 1932), Poslední cesta presidenta Osvoboditele T. G. Masaryka (Last Journey of the President Liberator T.G. Masaryk, 1937), Jásající město (Cheering City, 1938), Pražské baroko (Prague Baroque, 1939), Svatý Jiří na hradě pražském (Saint George at the Prague Castle, 1939), Věčná tma (Eternal Darkness, 1940), Rytmus (Rhythm, 1941), Bílá Telč (White Telč, 1948), and Velikonoce na Slovácku (Easter in Moravian Slovakia, 1948). Furthermore, he was involved in Defilé (The Parade, 1940–1941), eight-volume film magazine on culture. At the end of German occupation he experienced short-time imprisonment in interment. During the Prague uprising he was out in the streets together with his colleagues, their pictures were later used in Otakar Vávra’s movies Vlast vítá (The Homeland Welcomes, 1945) and Cesta k barikádám (The Journey Towards Barricades, 1946). After 1945, his involvement in filmmaking was significantly limited (and three years later he finally stopped it) and instead he shifted his focus on pedagogy, science, theory and technical organisation.

He made also significant imprint in our National Technical Museum in Prague Letná. Head of Technical Department since 1923, he founded Photography-Cinematography Department and launched its first public exposition in 1925. He was ambitious and passionate in completing these collections with recent cinematographic devices, related technology and artifacts at national as well as international levels from the earliest period (when not able to get the original device, he provided for its copy – model ‑ fabrication). It was also at his incentive the museum received part of estates of Jan Kříženecký, founder of Czech cinematography, including his Lumiere-style camera. Under the National Technical Museum he founded the first Museum of Cinematography in Prague Letná (1948) which later disappeared. Furthermore, he was also involved in organizing festivals and several exhibitions (in his role of Exhibition Committee Chair), such as 50 let kinematografu (50 Years of Cinematograph, 1945), 50 let československého filmu (50 Years of Czechoslovakia Film, 1948) and many other. Indeed, the first exhibition mentioned above was later used as a background for document 50 let kinematografie (50 Years of Cinematography, 1946) by František Sádek.

In 1943, when Bohemian-Moravian Film Union founded film archive, its direction was assigned to W. G. Lohmayer, of German nationality. However, Brichta, nominated as deputy director, had prepared all technical, operational and specialized issues of this body. His team members were young people passionate in the field, who were to become leading persons in cinematography: film historians Myrtil Frída or Luboš and Šárka Bartoškovi. When German occupation ended, he took the position of the archive director (1945–1951), the archive having been associated under Czechoslovak Film Institute. Furthermore, Brichta is also credited for having entered the institute into international federation of film archives, FIAF. He made a number of study trips across Europe and established networks with French, US, English. Danish, Polish or USSR specialists in the field.

Since 1946 he was lecturer at Prague Film and TV School of the Academy of Performing Arts (FAMU), teaching the following courses: history of film technique, basics of camerawork, and film tricks. He lectured there until his death. In 1956 he was granted “Docent” title. Furthermore, he taught history of film technique also at Higher Film Professional School in Čimelice by Písek (1952–1956). All his life he engaged in holding lectures for different kinds of institutions targeted for specialized audience as well as for the general public. In mid-1950s he definitively quit our film ateliers, being specialized advisor for Oldřich Lipský retro comedy Vzorný kinematograf Haška Jaroslava (Jaroslav Hasek’s Exemplary Cinematograph, 1955).

As for the field of opinion journalism and publications, Brichta is author of a number of studies and articles published in both specialized and pop-science periodicals on national as well as international level (i.e. on biologist Jan Evangelista Purkyně, having proven that the latter was also involved in the invention of cinematograph as one of its pioneers). He made entries for Ottův slovník naučný nové doby (Otto’s Encyclopedia of the New Era), Technický slovník (Technical Dictionary) and Malý filmový slovník (Small Film Dictionary). Only a small fragment of his research work did he manage to publish in print, such as Stručné poznámky k přednáškám o dějinách fotografie (Brief Notes on History of Photography Lectures, 1950), as well as various prologues for books by his colleagues, papers in anthologies, university textbooks, exhibition catalogues, etc. His long-time prepared monograph Edison ukázal cestu (Edison Showed the Way) was published only two years after his death.

Just shortly before his death he was involved in Jaroslav Brož and Myrtil Frída’s publication Historie československého filmu v obrazech 1898–1930 (History of the Czechoslovak Film in Pictures 1898‑1930, 1959), having provided some picture material, reviewed the manuscript and wrote texts for the first forty-one pictures dating back to Czech films early stage. Finally, the authors dedicated the book to the memory of Jindřich Brichta. Indeed, Brichta’s life and work would be commemorated in various books, as in Václav Wasserman’s memories Václav Wasserman vypráví o starých českých filmařích (Václav Wasserman Talks about Old-Time Czech Filmmakers, 1958) and in anthology Průkopníci čs. kinematografie VII. Jindřich Brichta (Pioneers of Czechoslovak Cinematography VII. Jindřich Brichta, 1959), or as did e.g. Myrtil Frída and Adolf Branald in newspaper articles or Luboš and Šárka Bartoškovi or Martin Štoll in their dictionary entries.

In 1937, Brichta married Milada Kafková and they had two daughters: Jindřiška Brichtová-Skalická (born in 1942) and Marie Brichtová-Vozábová (born in 1947), the latter worked later in the film archive. In 1955, on the 10th anniversary of film nationalisation, Brichta was awarded the Order of Labour for “extraordinary activities in the field of film documentation, in particular for the foundation of the Cinematography Museum”. One of our prominent pioneer personalities of the film, Brichta died suddenly of heart attack in Prague on 6 June 1957, just twenty-one days before his sixtieth birthday. He left us huge legacy. Today, his personal estate is preserved in part in the National Technical Museum and in part in the National Film Archive.

This is how Myrtil Frída remembered his colleague Jindřich Brichta a few years later:

“He was able to get his teeth in any technical problem with exemplary tenacity. He would not stop until he had found, or literally sniffed out, the very last detail, indeed he would follow it at the end of the Earth. There was no day, no evening, no moment he would not be working on something connected with cinematography. He was writing specialized as well as pop-science articles, he was giving lectures, making notes, talking on the phone, collecting disappearing memories, yet always he would find some time for a friendly chat, talking with his friends about his big love. He would be talking, telling stories, gesticulating, painting on a scrap of paper and searching feverishly in a drawer to take out one of thousand pieces of evidence to support his statements. […] He was the soul of all activities, he knew about each hidden film, about photographs, labels and memories of cinematography pioneers whose preservation and transfer […] were not to be postponed with the risk of their getting lost every moment. Brichta should be credited for having managed all this and for being ten to fifteen years ahead of time, indeed the following archives would not catch up with it later on.“[2]

Notes:

[1] In this movie he also portrayed a member of invitation committee.

[2] Frída, Myrtil, Vzpomínka. Záběr X, 1977, No. 12 (3. 6.), p. 6. Srov. Knor, Valentin – Frída, Daniel (eds.): To je mi pěkná historie. Vzpomínka na Myrtila Frídu. Praha 1989, pp. 154–156.