Nationwide distribution of the film Joseph Kilian (Postava k podpírání, 1963), which was shot by Pavel Juráček and Jan Schmidt, started on 4 September 1964, that is, almost half a year later after its success at the tenth short film festival in Oberhausen, where it was awarded the Grand Prize. Early reviews of Czech critics were thus based either on a limited distribution of the film in its homeland or on its projection at the festival. The first review by Vladimír Bystrov is, for instance, a proof of the film´s projection at the Short Films Cinema at the Wenceslas Square in January 1964. Besides his astonishment by the film´s name, Bystrov in his text probably reacts to the film´s annotation in the Filmový přehled magazine, which links him with the work of Franz Kafka: “A medium length motion picture film, described by its author as a “Kafka´s depiction of absurd situations related to the cult period, the absurdity of which we were unable to realize.”[1] However, Bystrov somehow belittles the link between Juráček´s film and the poetics of Kafka´s works: “It would be exaggerated to compare the world of Joseph Kilian with the world of heroes in Kafka´s novels.”[2] He then captures the film´s message differently, by quoting Bruno Jasieński: “but it is absolutely necessary to show the film´s connection with the famous sentence: do not fear your enemies, do not fear your friends, fear the indifferent.”[3] Filmový přehled takes over Juráček´s confession about “Kafka´s depiction” in Joseph Kilian from his interview for Filmové informace,[4] that went public on 26 June 1963 when the film was already being shot[5]. Nevertheless, Juráček later both publicly and privately defied the connection with Franz Kafka´s work. In an interview for the Kino magazine a year and a half later he said: “Had Jirásek been fashionable at that time, we can expect that, he would have been discussed as a connection with Joseph Kilian. As a matter of fact, Kafka is also discussed in relation to Ionesco, Beckett, Adamov, Camuso, Mrožek etc.“[6] In his earlier private writing (21 September 1963) he also states a possible motivation for the change in the way of presenting his debut: “It occurs to me that I will soon start hating Kafka. And only here on this page I dare to say that I have never read neither The Trial, nor The Castle. But today I know that I will try and get Joseph Kilian rid of epigonic accusations.“[7]

In 1962, when Juráček was creating the main theme for Joseph Kilian, Kafka didn´t belong to officially tolerated authors, even though, it was possible to interpret him more positively after 1956 than in the first half of the fifties.[8] Apart from studies in magazines [9], a Czech translation of The Trial came out at the end of the fifties [10], but after 1958, another wave of cultural and ideological tightening took place. The possibilities of Kafka´s less restricted reception began to improve again only in 1962 when an initiative to hold a conference on Kafka in the town of Liblice was formed, which eventually took place between 27–28 May 1963.[11] This means that Juráček was writing his preparatory literary texts for Joseph Kilian in a time favourable for innovations and crucial deeds, but nevertheless, Kafka´s work at that time was still a taboo in a way since the perception still hadn´t shifted towards the official Marxist viewpoint. This is, for example, supported by memories of a publicist Alexej Kusák from the Czech Germanists Commission meeting (23 November 1962), which was preparing the Kafka conference: „[Eduard] Goldstücker (…) the suggestion to organize a conference on Kafka led to limiting the event to “our private meeting of Marxists” who would first need to agree on a common stance on how to interpret Franz Kafka´s work.“[12] When Juráček marked his first (literal) versions of Joseph Kilian as Kafkaesque[13], it could have been perceived as non-conforming at that time and only as a result of the success of the Liblice conference, which allowed for reintroducing Kafka´s work into official discourse, marked the film with the feature of epigonism.[14]

If we look back at how Vladimír Bystrov sees the film in his first review we will realize that he was unknowingly accommodating Juráček´s problem with epigonism. It is also possible that his desire to get the film rid of Kafkaesque mark was driven by a press affair about the Kafka Conference which was provoked by an Eastern Germany politician Alfred Kurella in his article “Spring, Swallows and Franz Kafka” published in a cultural magazine Sonntag.[15] Kurella very fittingly describes the situation with his own words in a letter to editors of an Italian paper Il Contemporaneo as cited by A. Kusák: “My article in Sonntag was a political article. It was directed against political reception of the Prague conference as a turning point in the Marxist way of thinking and against political assessment of our era as a state of society, for which Kafka provides the right interpretation. Garaudy[16] (…) is the author of those two political statements (…) and I couldn´t have stayed silent. Especially because in his article he broadens the meaning of the term alienation, which must make every expert on thinking of our classics furious…”[17] Bystrov, as if being careful about the situation at that time, changed the controversial part in Joseph Kilian hidden in its announced “Kafkaesque depicting” when he used a “belligerent” epigraph by Bruno Jasieński, a rehabilitated communist author, to describe the film. As for the depth of Juráček´s work he then added: “Joseph Kilian is a short film with a big idea delivered in a brave and particularly funny hyperbole. (…) it is already time it started screening in other places too.”[18]

A similar hint about the limited distribution of the film was also made by Jiří Pištora at the end of his review for the Tvář magazine when he brought up the thought whether the film´s distribution is aware of the film´s underlying criticism or not: “Does also the film distribution know, what is going on? I am not quite sure; putting this grand short film innocently on the slapsticks programme in the cinema Praha (…). Or, perhaps, they know too well? “[19] Pištora keeps this bold tone throughout the text, for example when he haughtily states that: “Hardly anyone is going to overestimate this film in our country. “[20] His conviction stems from a comparison with Věra Chytilová films, which, according to Pištora, are already hard to comprehend for an “ordinary film viewer”, and which, in comparison with the effort put in Joseph Kilian´s film philosophy, look really simple, regardless of all their indisputable quality. Pištora thus interprets the film´s overall message as a deeply philosophical view on “the modern world in its complexity, or better, in its system. (…) The authors see what remained of Kafka´s world in today´s reality, they draw today´s conclusions. (…) In my opinion, we can rightfully blame them for Karl Marx´s influence, whose touch I can feel here just as intense.”[21] There, we can see an analogy, when Pištora, just like Bystrov, wants to protect the film´s message which could have been endangered by the words about “Kafkaesque depicting” from the Filmový přehled annotation. To both Kafka and Marx he assigns the same level of influence.[22] And the “classic” to whom also A. Kurella refers to in his criticism of the Kafkaesque conference results and whose term “alienation” was in Kurella´s opinion used in Kafka´s interpretations too much.[23] This means that Pištora notices the same connections between Marx and Kafka as some of the contributors of the Kafkaesque Conference but he chooses to observe them individually instead of trying to logically link them, since that could have been seen as an effort to provoke the advocates of “pure socialism”, such as Kurella was.

It was mainly Jan Hořejší who wrote about Joseph Kilian´s success at the Festival in Oberhausen in the Czech press, but regardless the nature of his two articles, which both described the festival in general, he covered only fragments of the film. Nevertheless, as cautiously as his colleagues: “It was only in Prague where I learned about thoughts on how good or how bad it was that a socialist film as critical to its own flaws in the past as Joseph Kilian had won a competition held in West Germany. (…) At Oberhausen festival there was a jury, which, apart from Karel Zeman, composed of other important filmmakers from socialist countries, whose job was to assess the artistic and intellectual quality of Juráček´s and Schmidt´s film. Is it possible to assume that this “gathering” awarded our film a prize with some ulterior motives or even for some of its “suspicious” features? If the audience in Oberhausen liked the film because of its, let´s say fashionable, Kafkaesque tune, I don´t find it that bad, but the jury, on the other hand, appreciated mainly what the film fights for with youthful vigour – for better world without prejudice, without schemes.“[24] Hořejší also assumed a specific strategy on how to avoid connotations with Kafka by strictly distinguishing between perceptions of the western audience, who perceived only “fashionable, Kafkaesque” tunes of the film, and the opinion of the festival jury, composed of filmmakers from socialist countries (Hořejší deliberately omits other jurors), who were concerned not with the film´s rendition, but mainly with its message, with what it “fights” for. However, Hořejší doesn´t say much about the film´s message itself since he puts it in a certain timeless zone; first he speaks about the film´s criticism towards the past by which he is probably alluding to the cult of personality, then he mentions a general aspect that the film shares with the socialist art – “solving problems of our lives” – and finally he examines the film´s contribution to the socialist future, how it can help co-create “the better world without prejudice, without schemes”. In his second article, Hořejší assumes even more moderate position towards the film which is also demonstrated by showing his sympathy: “the film is young not only because of its age but also because of its thoughts.“[25] Another person who wrote a report on the festival in Oberhausen was Jan Žalman. However, apart from pointing out Joseph Kilian´s resemblance with Kafka, his article is void of any interpretation of the film´s message and focuses above all on a general celebration of a young generation of filmmakers. If compared to Hořejší, Žalman´s statements are even vaguer: “What was ruined by not very successful introduction of the film in Prague was made up by Oberhausen, regardless the concerns about untranslatable passages, regardless the concerns about its form. (…) Juráček´s film reasserted every perceptive viewer (…) that both the young and the youngest generation of our filmmakers hadn´t missed their chance; that they have things to say and that they know how to say it.“[26]

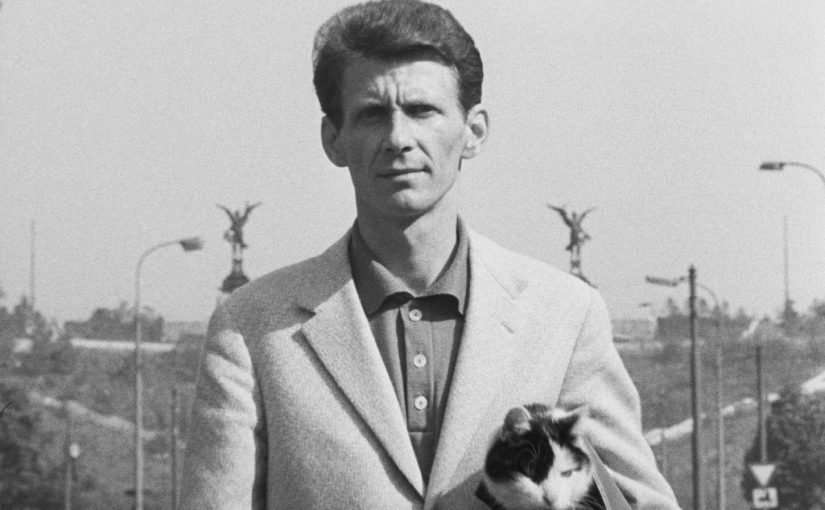

Possibly the most extensive period review of the film is the article by Eva Šmídová in Film a doba, which is also preceded by the interview with Pavel Juráček taken by Josef Vagaday. He presents Joseph Kilian together with the film When the Cat Comes (Až přijde kocour) as the most socially committed films of the preceding year´s production. He also adds the missing piece of the text written by Jan Hořejší: “What he talks about does not only refer to the recent past.“[27] Šmídová, unlike Hořejší and previous critics, explains the film´s meaning sufficiently and by no means avoids to point out similarities between the film and Kafka, or to talk about alienation: “This is about nothing more or nothing less than two authors contemplating some of the features of the personality cult, mediated by the principles of Kafkaesque absurdity. The cult of personality period with its typical features, some of which have often stayed in the minds of individuals up to this day [accentuated by K. M.], can be captured and expressed by various methods and ways, as shown by a number of pieces of art today. The film makes it obvious that the authors of Joseph Kilian weren´t interested in descriptive portrayal of individual, more or less shocking cases, but rather in expressing the atmosphere of that time coming from alienation. Uncertainty, impossibility to understand, nonsensicality, internal contradiction between a man and the society – these all constitute the basis of absurdity. Thus, it was no coincidence that the authors chose to show Joseph Kilian from this viewpoint, since it helped them to shed new light on the phenomenon, on the period, on a man.“[28] The key feature, which makes critical expression possible, is again not placing the object of criticism into the present, or at least not explicitly. First, it is important to assure readers that the film deals with nothing more than the time passed, then, in the second sentence, there is unwittingly mentioned that some of the cult of personality features can be “every now and then” found also in the present. The third sentence brings deliberate ambiguity by using the words “of the time” – the period “optimists” will probably see it as a link to the past, because that´s the only time where such “more or less shocking cases” could have taken place, the rest of recipients will probably see the obvious connection with the time present. The last sentence then includes the adverb “new” to assure the readers that we are still talking about the time passed, since it puts certain distance between the sentence object and subject.[29] Šmídová indirectly promotes Juráček´s and Schmidt´s work as a scientific document which follows Marxist dialectic methodology – the object of interest is the alienation which is the product of the personality cult, the method of solution is depicting the alienation through the principle of Kafkaesque absurdity, which brings this absurdity into more general plane and breaks the conventional connection with Kafka´s work. A new look at the phenomenon, that has already been discussed several times, enables new understanding, new synthesis and (theoretically) its practical elimination, which has already partly happened because it is almost not being connected to the present anymore.[30]

One month later, an article similar to feuilleton by Ivan Soeldner comes out, where the author points out the principle of communicating the truth through comic drama and film means. And it is Joseph Kilian that he perceives as the most powerful comedy or satire of the time, which in his opinion doesn´t lack the more specific tie to the present unlike the obvious film When the Cat Comes, and with its criticism can match theatre plays like Dragon is a Dragon (Drak je drak) by Satirické divadlo Večerní Brno and Citizen Čančík (Občan Čančík) by Divadlo Komedie. Soeldner criticises viewing Joseph Kilian at the time as Kafkaesque drama and just as previous critics gets fully explicitly rid of the stigma, which the Kafkaesque feature brings to the film: “It is a comedy – and also here the smile freezes on one´s lips. That is why many see the film as a Kafkaesque drama and even hold the influence of Franz Kafka against it. But did Kafka have any sense of humour? (…) Joseph Kilian is a satire which shows maladies of socialism, it is completely accurate, accustomed to the time and fully blended in it. (…) no mystical fear of alienation, it is a wonderful, humorous satire about a “strange” alienation of our bureaucratic world. Most of all: it is a view of ironic people, humourists in the most serious sense of that word. Direction a film satire should follow.“[31] Soeldner´s words about the “inexistence of the mythical fear of alienation” however somehow wipe off the socio-critical appeal of the film, which Juráček probably had in mind from the very beginning when he deemed the film as an indirect attack on the norms of the time through the connotations with Kafka, because he was aware of the danger that the film might be accused of formalism, which later indeed happened, partly thanks to the mark of Kafka.[32] Soeldner´s article thus somehow contradicts itself at the end, when it eases the Joseph Kilian´s criticism to a “wonderful, humorous satire about a strange alienation”, which probably isn´t really alienation, because it is “ours” and because it is played by ironic people and humourists who are only doing their job.

More critical reviews of the film brought the autumn of 1964 when a nationwide premiere took place and the film was awarded a prize in Mannheim. However, only texts by Pavol Branko (1 September) and Antonín Jaroslav Liehm (7 November) address the film´s overall message. Although the review by Branko doesn´t link the film with Kafka´s legacy anymore, Liehm does so again, but this time moves it from the context plane to the formal one. Branko appreciates the film´s authors for: “focused attack against the deepest principles of the cult, which is only seemingly linked with contradictory anonymization of the authorities and their detachment from those they control. It became a battering ram against the strenuously spread prejudice, that we are not really serious about the destruction of the personality cult. However, the prejudice is very flexible and can accommodate easily. In this particular case we had to ask ourselves a tough question whether we were going to screen the film in our country or whether it was only good for export. Obviously, it wasn´t…”[33] Unlike his colleagues, Branko already uses present simple when speaking about the personality cult and openly expresses the essence of this social/political phenomenon and the context of the discussion about it at the time – a dispute whether it still exists and whether there is anyone able to look for its solution in real life. And it is Joseph Kilian who in Branko´s opinion provides the “activation” that brings forth the solution through the social awareness: “we experience the film as a metaphor of something long past, but at the same time its intellectual level is revealed to us in dozens of short connections with tough life and which surrounds us in ever new forms. However – we do realize its absurdity now and Joseph Kilian speeds this process up, accelerates it and makes us allergic to its scenes, unwilling to tolerate them any longer. Thus, it was not only a result of a critical perspective, looking into a distorted mirror of the time, but also an effective activation…“[34]

Antonín J. Liehm, on the other hand, doesn´t perceive the film through the lenses of the personality cult and, as a result, doesn´t see it as a solution to the social problem of the whole society, but mere as a portrayal of a problem of a specific social group. However, his text is obviously not meant to inspire tolerance from the majority, but rather to explain the film as its manifestation, which doesn´t have to be heard out, since it is enough when “the people” solve it in themselves: “There are young people in this world, in our world, and I don´t want to guess whether there are many or few, with the feeling that this film expresses. The feeling is not good, not normal, it is dangerous, but they haven´t made it up, it really does exists, it smothers them and those alike, and they just don´t know what to do about it, how to overcome it, how to get out of it. It might be their fault, but not theirs only. And so in the end they decide to express the feeling, to speak about it aloud, for themselves and for others. And it is a positive deed, since once performed, this feeling ceases to be something undefinable, abstract, dangerous; its expression is also a mean of overcoming it in a way, it also brings forth laughter, laughter is liberating, releases inner stress it was born of, shows the way from negative to positive, it is the first step to finding a way out, as any form of self-awareness, anyway. So a deed which is neither optimistic nor pessimistic in its meaning but positive for sure.“[35] Liehm´s dialectic approach to the analysis however doesn´t explain the origin of such felling about life, which those people, looking from the distance, have, since this explanation might be an analogy to the official interpretation of Kafka´s scepticism, which Marxists interprets clearly connected with capitalistic environment,[36] that might lead to a dangerous paradox. It also justifies the fact why they see the link between Joseph Kilian and the work of Kafka only at the formal level, whereas by the form they probably mean the use of Prague´s stage set: “It has been said a hundred times that Kafka is defined by his time, his environment, his triple isolation, era etc. (…) And then, suddenly two young people appear in Prague, in the town of Kafka, who are only a little bit younger – if really – than Kafka was when he was writing some of his famous works. They know the town as well as he did and for many reasons they also have the absurd feeling, although in a completely different time and based on completely different grounds, and everything pushes them to see the world around them in a grotesque light. They do not intend to imitate Kafka, nor do they particularly think about him. But the town, its streets, palaces, houses, all of it gradually imposes their work a form that will eventually remind us of Kafka.“[37]

Thus, Liehm´s opinion sounds as a contradiction to the opinion of V. Bystrov in the first review, who, at the beginning of the year, saw the search for similarities between the two worlds as exaggerated, which might point to the strength of the influence of the perception at that time and the frequent use of Kafkaesque comparisons on the following reception of the film. However, it was those comparisons that allowed the terms alienation and indifference to penetrate into the period discussion about the film, which, in the socialist environment of the time, would probably give the impression of being too bold or too provocative. The existence and the cause of those phenomena, however, had to stay mainly in the “unvoiced, implied” zone, or only in relation to the fading personality cult. The connection between Joseph Kilian and Kafkaesque poetics, as declared by Juráček, could have also been perceived in Czechoslovakia as something fashionable thanks to the development of the film´s reception, which was used by some people (e.g. Federal Security Service) as a mean to downplay the message of the film or its narrative and stylistic innovations. It is no surprise that contemporary reviews also mention the connection between the film and Kafka[38], however, the question, whether Joseph Kilian was an innovative act, or just took over a fashionable idea, will probably never be fully answered.

Notes:

[1] Filmový přehled: týdeník pro kulturní využití filmu. Praha: Československý státní film, 6. 1. 1964, no. 1, p. 5.

[2] by [Vladimír Bystrov]. Neobyčejný film. In: Svobodné slovo20, 29. 1. 1964, no. 26, p. 3.

[3] Ibidem. B. Jasieński (1901–1938) was a representative of Polish literary futurism. He lived through the second half of the twenties in France, from which he was expelled for publishing a futuristic novel Palę Paryż (Pálím Paříž, 1928). He then moved to the USSR where he became a respected author. However, due to his sympathies with Genrich Jagoda he was later executed during the Great Purge. He was rehabilitated in 1956. Bruno Jasieński. Last update 23. 3. 201911:05 [cit. 31. 3. 2019], Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bruno_Jasie%C5%84ski. The quote by Jasieński comes from the introductory epigraph in the book called Spiknutí lhostejných. Its full wording goes as follows: “DO NOT FEAR your enemies. The worst they can do is kill you. “DO NOT FEAR your friends. At worst, they may betray you. FEAR those who do not care; they neither kill nor betray, but betrayal and murder exist because of their silent consent.” JASIEŃSKI, Bruno. Spiknutí lhostejných. Praha: Mladá fronta, 1958, p. 18.

[4] The questions by FI were answered by a young screenwriter Pavel Juráček. Filmové informace 14, 1963, no. 26, p. 13.

[5] The shooting took place from 20 June to 19 July 1963, see JURÁČEK, Pavel. Postava k podpírání: (groteska 1962–1963). Praha: Knihovna Václava Havla, 2016, p. 10.

[6] VRAŠTIAK, Štefan. O postavě, kterou bylo třeba podepřít. An interview with the director P. Juráček. Kino 19, 19. 11. 1964, no. 23, p. 11.

[7] JURÁČEK, Postava k podpírání, p. 144.

[8] Alexej Kusák quotes an article by Howard Fast from 1951 to demonstrate that Kafka´s work was perceived negatively:” (Kafka) is sitting atop (…) cultural reaction dunghill” and proclaims “an equation of German fascism (…) man equals a cockroach.” KUSÁK, Alexej. Tance kolem Kafky: liblická konference 1963 – vzpomínky a dokumenty po 40 letech. Praha: Akropolis, 2003, p. 8.

[9] DUBSKÝ, Ivan – HRBEK, Mojmír. O kafkovské literatuře. Nový život, 1957, no. 4, pp. 415–435. EISNER, Pavel. Franz Kafka. Světová literatura 2, 1957, no. 3, pp. 109–129.

[10] KAFKA, Franz. Proces. Praha: Československý spisovatel, 1958. 225 p.

[11] For more about the conference, see KUSÁK, Tance kolem Kafky, pp. 7–62.

[12] Ibidem, p. 19.

[13] See Juráček´s note from 11 November 1962: “I am now writing such a strange film – I have to say a film, since it has nothing to do with the written word – a kind of an existentialist grotesque or Kafkaesque grotesque which is about eight hundred metres long.” JURÁČEK, Pavel a KRATOCHVÍLOVÁ, Marie, ed. Deník. III., 1959–1974. Vydání první. Praha: Torst, 2018, p. 303.

[14] In my semi-finished dissertation thesis I deal with Pavel Juráček´s author intention and more detailed relations of how his debut was received as a piece of work which draws from Kafka´s poetics.

[15] A Czech translation came out in Literární noviny: KURELLA, Alfred. Jaro, vlaštovky a Franz Kafka. Literární noviny 12, 5. 10. 1963, no. 40, p. 8.

[16] Roger Garaudy – a French philosopher, member of the French Communist Party politburo at that time, attended the Liblice conference.

[17] KUSÁK, Tance kolem Kafky, p. 69.

[18] by. Neobyčejný film, p. 3.

[19] PIŠTORA, Jiří. Setkání s dílem. Tvář 1, 21. 2. 1964, no. 2, p. 29.

[20] Ibidem.

[21] Ibidem.

[22] About Marxist connotations in Postava k podpírání also see HUDEC, Zdeněk. Marx, nejenom Kafka: odcizení v Postavě k podpírání. In SCHNAPKOVÁ, Andrea – HUDEC, Zdeněk. Postava k podpírání. Praha: Casablanca, 2017, pp. 78–95.

[23] A. Kusák explains in what aspects where those analogies relevant to the work of Marx. “The topic of alienation appeared in discussions about Kafka while scrutinizing the content of his works. When researchers wanted to investigate what it is Kafka actually writes about, they couldn´t evade one of the basic questions of the modern industrial society. In his earlier and later works, Marx offers the answer by developing the philosophical problem of alienation. It then becomes uncomfortable when socialist states start assuming that by nationalisation of the industry and trade the essence of alienation had disappeared. Those who have personally felt that it was not the case, but quite the contrary, that the elements of alienation started manifesting in the opacity of state administration, in bureaucratization and in adopting brutal methods of suppression, those are all beginning to find in Kafka´s works an author, who seems as if he was anticipating situations in which they are finding themselves at the moment.” KUSÁK, Tance kolem Kafky, pp. 68–69.

[24] HOŘEJŠÍ, Jan. Oberhausenský jubilejní… Práce 20, 20. 2. 1964, no. 44, p. 5.

[25] HOŘEJŠÍ, Jan. Velká cena oberhausenské Cesty k sousedům. Kulturní tvorba 2, 20. 2. 1964, no. 8, p. 16.

[26] ŽALMAN, Jan.Postava v Oberhausenu. Literární noviny 12, 21. 2. 1964, no. 8, p. 12.

[27] VAGADAY, Josef. Jeden z nových. Film a doba 10, 1964, no. 3, p. 138.

[28] ŠMÍDOVÁ, Eva. Nejen půjčovna koček. Film a doba 10, 1964, no. 3, p. 139.

[29] Using the attribute “new” together with a multiple object would have the opposite effect: The viewpoint helped them to shed light on the new phenomenon, time and man.

[30] Šmídová, however, has no doubt that the problem can be solved.

[31] SOELDNER, Ivan. Náš přítel smích. Film a doba 10, 1964, no. 4, p. 201.

[32] This is evidenced by Juráček´s remark from 24 March 1963 regarding the upcoming defence of the film before the artistic council of the creative group Fikar–Šmída: “It is headed to the artists´ meeting the day after tomorrow and everyone says in advance that it will be rejected because it is unintelligible and formalistic.” JURÁČEK. Postava, p. 87.

[33] BRANKO, Pavol. Nepolapiteľná postava polapená. Film a divadlo 8, 1964, no.18, p. 8.

[34] Ibidem, p. 9.

[35] ajl. [Takový malý film…]. Literární noviny 13, 1964, no. 45, p. 8.

[36] “The work of Kafka, as anything that is of significance in the culture of man, will be “annulled” by victorious Marxism: it will be possible to understand it historically and then use it for more history. The unease that many socialist still feel about Kafka up to this day will vanish in proportion to how those socialists will remove alienation from the world.” SCHUMACHER, Ernst. Kafka očima nového světa. In: REIMAN, Pavel, red. Franz Kafka: liblická konference 1963. Praha, 1963, p. 242.

[37] ajl, [Takový malý film…], p. 8.

[38] The majority of current interpretations comes from critics and historians who were affected by the reception of that time or created it themselves – Jan Žalman, Antonín J. Liehm, Josef Škvorecký, Jiří Cieslar, Jan Lukeš, Stanislava Přádná.