Svěrak’s 80th birthday will be celebrated in great style. A remastered version of Obecná škola (The Elementary School) will be screen in selected theatres in the Czech Republic and around the world on his birthday. This autobiographical family tragicomedy from post-war Bohdalec belongs to one of the many works of the father-son duo Zdeněk and Jan Svěrák. In the same year, 1991, it was also a representative example of a domestic, post-Revolution film – clever, nice and Czech. These three adjectives characterize a host of other screenplays written by Zdeněk Svěrák.

The father/screenwriter and son/director are also responsible for the most award-winning post-Velvet Revolution film Kolja (Kolya), which won the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar in 1997. The Svěráks’ joint filmography includes six feature films, the last of which was the fairy tale/ comedy Tři bratři (Three Brothers), which premiered in Summer 2014. During the March celebrations, it will be officially announced that Jan Svěrák will begin filming his father’s memoires Po strništi bos (Barefoot Across the Stubble), the screenplay for which was also written by Zdeněk. According to the official rankings compiled by the Association of Czech Bookshops and Publishers, the memoires were the best selling new publication in 2013. “It is me and it isn’t,” declared Zdeněk Svěrák about the book, which was inspired by his memories of one summer as a boy. Timewise, the story takes place before the time of Obecná škola. It recounts the experiences of the seven-year-old protagonist who had to leave the Prague neighbourhood of Bohdalec for two years with his parents to live in the countryside in his father’s home village of Kopidlina. The relatively short timeframe belongs to one of Svěrák’s most formative periods; at the same time, however, it includes an interesting period in modern Czechoslovak history.

Zdeněk Svěrák has shown that combining “major” history with minor personal events can create a rich story, regardless of whether it takes place in a specific historical period [Život a neuvěřitelná dobrodružství vojáka Ivana Čonkina (The Life and Extraordinary Adventures of Private Ivan Chonkin), Tmavomodrý svět (Dark Blue World), Obecná škola (the Elementary School) and Kolja (Kolya)] or in a fictional, fairy tale world [Tři veteráni (Three Veterans), Lotrando a Zubejda, (Ruffiano and Sweeteeth), and Tři bratři (Three Brothers)]. The fictional character of a national genius, Jára Cimrman, is a specific part of the author’s journey back into history in two films: the comedic thriller Rozpuštěný a vypuštěný (Dissolved and Effused), based on the play Vražda v salonním coupé (Murder in a Parlour Car Compartment), and the super mockumentary Jára Cimrman, ležící, spící (Jára Cimrman Lying, Sleeping).

Zdeněk Svěrák kept an ironical, merciless and loving distance not only from his heroes from the past but also from his current characters. Beginning with the title protagonist from the comedy Jáchyme, hoď ho do stroje! (Joachim, Put It Into The Machine!, 1974) and ending (for the time being) with the lively pensioner Josef Tkaloun from Vratné lahve (Empties, 2007), Svěrák uses them to tell stories – regardless of who directed them – about “ordinary Czechs”.

Svěrák makes use of the child’ view of the world (Kolja, Obecná škola); however, confrontation between a child and an adult protagonist is import for his positions [the only exception perhaps is the comedy Ať žijí duchové! (Long Live Ghosts!, 1977), but its character is of course influenced by Jiří Melíška’s book]. No women play heroes in Svěrák’s work, even though his stories cannot do without the fair sex: Svěrák’s heroes could not exist without the practicality, loving devotion and tolerance of their women. Faithfulness plays an important role in their lives, which, however, can only work in confrontation with temptation. There is a desire in each of Svěrák’s heroes not always to behave morally and to let himself be swept away by his fantasies and forget that one day he will have to pay for it.

Svěrák’s stories are almost rigorously virtuous. The character to find himself furthest away from this rule was book seller Dalibor Vrána in the tragicomedy Vrchní, prchni (Waiter, Scarper!), but he was also punished most severely for his actions. It is therefore not by accident that the role of the womaniser who is haunted by alimony payments and commits peculiar crimes was not played by Zdeněk Svěrák, but by Josef Abrhám.[1] If Svěrák does lend his face to “his” heroes, it is always to those who follow established standards of morality, which the public associates with the author himself – even though, for example, musician Louka from Kolja or teacher-cum-pensioner Tkaloun from Vratné lahve first have to undergo temptation. Svěrák’s new protagonists are, of course, more morally clean-cut than, e.g., the somewhat ambivalent heroes form the 1980s, when Svěrák was directed by Vít Olmer. Whereas dentist Burda from the tragicomedy Co je vám, doktore? (What’s Up Doc?) is the protagonist of Svěrák’s screenplay, engineer Hnyk from the film Jako jed (As Good As Poison) is the exception to Svěrák’s filmography because he was written by other authors – Olmer and Jiří Just – according to Karel Zídek’s book.

It is worth noting that none of Svěrák’s heroes are “weaklings” in the sense of the characters brought to Czech film by the new generation of directors after 1989. Although the father in Obecná škola or Louka have to bend their back, their moral code is not distorted, they are fully socialised, their relationships to their surroundings are not disturbed by egocentrism – and they are never passive. An example of this is the final scene in Obecná škola, in which the father of the young hero diffuses an unexploded grenade on a school fieldtrip, whereas the pompous war hero Igor Hnízdo fails pathetically.

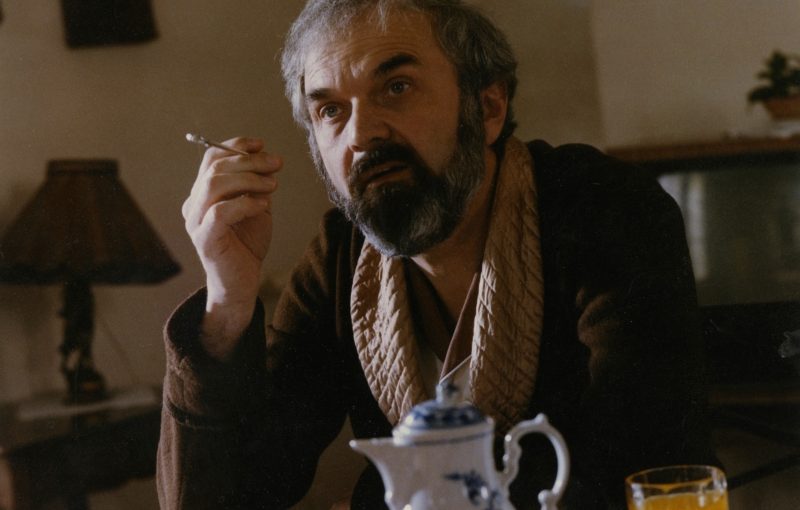

At least since the early 1990s, there began to appear a certain stereotype connecting the “real” Svěrák with the “Svěrák-esque” character. This connection is especially strong at the moment when son Jan directs his “dad” [Tatínek (Daddy) is also the name of the biographical feature documentary from 2004, which was co-directed by Martin Dostál)].

The head of the family in Obecná škola (which is in fact is a remembrance of Zdeněk’s father), healer Fišárek in Akumulátor 1 (Accumulator 1), Louka and Tkaloun are all tied to their creator in a similar way that “Allen-esque” characters are to Woody Allen. Even the puppet story Kuky se vrací (Kooky) was narrated by a “Svěrák-esque” character: the wise and gentle forest creature Hergot. Only in the genre film Tmavomodrý svět did Jan Svěrák not find a role for his father’s civilian acting style, so Zdeněk appears just briefly on the screen.

There is of course no purpose looking for the boundary line dividing construct from the imagined “real” Zdeněk Svěrák, who, as a writer, plays repeatedly with the respective situations: in the film about shooting the film Trhák (The Hit), he plays the screenwriter; in the film portrait about the theatre Divadlo Járy Cimrmana entitled Nejistá sezóna (An Uncertain Season), he then projects himself onto the character of writer and actor Rybník; and in the comedy Na samotě u lesa (Seclusion Near a Forest), he then plays Prague city dweller Lavička, who strives to buy a country cottage, which is based on an event from his real life. The casting of Zdeněk Svěrák as narrator/teacher in Tří bratři, a role that can be deemed iconic, was not by chance: Svěrák is in the eyes of the public a national celebrity that is in a way a “teacher of the nation” like Komenský and “father of the nation” like Charles IV. The pedagogical traits that Zdeněk Svěrák develops based on his education and original profession also dominate in the “character” of an author who sings his songs, set to music by Jaroslav Uhlíř with a youth choir.

The character of Svěrák/teacher is also credited to the role he plays in the pseudo-scientific seminars that are a regular part of the plays of the theatre company Divadlo Járy Cimrmana. The fictional character of this Czech genius, which Svěrák created with Ladislav Smoljak and Jiří Šebánek in 1966 for the radio programme Vinárna U pavouka (The Wine Bar U Pakvouka), is the subject of seminars organised by “scientists/criminologists” who act in theatrical pieces accredited to Cimrman himself. This explains their “amateur acting”, which of course is part of the act. Zdeněk Svěrák is in film a much more multifaceted actor than the “criminologist Svěrák”, who is moreover – as a caricature of a real, puerile, ambitious scientist – not very likeable. [2]

The general public have identified to a remarkable degree with the sophisticated game of this dual fictional world: Czechs with loving irony have accepted the character of Cimrman – who wrote in his diary: “I would like to see my homeland of Böhmen” – and nominated this fictional Austro-Hungarian genius in the serious national survey Největší Čech (The Greatest Czech) in 2005 [3].

Cimrman’s likeness may be unknown (only a bust exists, but the features are so distorted that his real likeness is indistinguishable), but thanks to the title role in the film Cimrman, ležící, spící, however, our idea of him mergers with the likeness of Zdeněk Svěrák himself [4]. A hypothetical model Czech viewer once wanted a prosthesis from Ladislav Chudík, the actor who played head physician Sova in the TV series Nemocnice na kraji města (Hospital at the End of the City). In the same way, the Czech public – without any ironic hyperbole – once dreamed of Zdeněk Svěrák being the Czech president. The respected birthday boy’s screenplays are the playground for more or less distorted mirror images of reality, in which, as part of one parallel reality, Svěrák is likely already president.

Notes:

[1] The “Svěrák-esque character” would surely be enriched by inspector Trachta, which Svěrák played on stage, but in the film Rozpuštěný a vypuštěný, directed by Ladislav Smoljak, the role was taken by Jiří Zahajský to the regret of the screenwriter.

[2] It is perhaps worth noting that in the 1970s, Svěrák and Ladislav Smoljak already created rather spiteful and subversive minor characters (e.g., the eternal classmates Šlajs and Tuček in the comedy “Marečku, podejte mi pero!” (Marecku, Pass Me the Pen!).

[3] Největší Čech is a format taken from the BBC. In Great Britain, even (mythical) King Arthur (but not, e.g., Monty Python’s Brian) made it into the top 100 “greatest Britons”. After consultation with their English colleagues, Czech Television decided to eliminate Cimrman from the nominations. Although the station never disclosed the number of votes he received, it is claimed he had a good chance of winning, besting the likes of Charles IV., T. G. Masaryk, Václav Havel, J. A. Komenský and Jan Werich (another Czech author who was a real “persona” for the public).

[4] And Valerie Kaplanová, an actress who plays an old custodian of the Liptákov Museum of Feathers who is in fact Cimrman, who turned into a woman in old age.