Already during his studies at the Film and TV school at the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (FAMU) in the first half of the 1950s did Valášek notice that Czech cinema did not have much to offer in the field of children’s film. His friendship with a slightly senior student, Milan Vošmik, [1] and his acquaintance with his fellow student Ota Hofman, with whom he later worked on several films, influenced in no small part his filmmaking ambitions.

During his studies, he filmed several short student films based on his own ideas and screenplays. In a reportage called Ženy v uniformě (Women in Uniform, 1954), he captures the life and work of women in the SNB (National Security Corps). The film Mladá láska (Young Love, 1954) tells a story about students falling in love. His thesis film V ulici je starý krám (There’s an Old Shop on the Street, 1955) is about a closed shop that some students want to turn into their flat. Although his first films are not devoted to children, his first job, assisting Jiří Weiss shoot the family film Punťa a čtyřlístek (Punta and the Four-Leaf Clover, 1955) set him off in this direction.

After graduation from FAMU, Valášek took employment at Československá televize (Czechoslovak Television), where compared to film, he had more of a chance to focus on his ambition to create work for children. “He is filming children’s shows, which have been growing in recent years. Be he is also producing game shows for youth and shooting films for TV,” [2] such as Chlapec a pes (The Boy and the Dog), Kuťásek a Kutilka na horách (Kuťásek and Kutilka in the Mountains), Léto v Tatrách (Summer in the Tatras), Malý svět (Small World) and the television adaptation of Mark Twain’s novel The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. [3]

Jan Valášek made his feature-film debut in 1959 with the children’s adventure film Prázdniny v oblacích (Vacation in the Clouds), which he filmed according to Ota Hofman’s screenplay based on Bohumil Říha’s popular children’s book O letadélku Káněti (A Plane Named Hawk). It tells the adventures of cousins Vojta and Pepíček, who, with their friend Anežka, are fascinated by a nearby airfield, where a pilot named Heyduk is testing the prototype of a new helicopter called Vážka (Firefly). The true adventure begins when they end up steeling it and flying up into the clouds.

In the spirit of the contemporary requirement imposed on children’s film, Prázdniny v oblacích received some criticism already during the approval process: “Many were shaking their heads about the preposterous notion of children flying off in a helicopter. For one, it has nothing to do with reality and is in fact so far removed that it is nonsense.” [4] And even reviews of the firm were not very favourable and demanded that such films be more educational. “The episode with the helicopter has unpleasant consequences for the pilot, but this is not illustrated sufficiently, nor is there a moral conclusion to the simple story about three friends.” [5]

Attention was paid to the absence of a clear moral conclusion despite Valášek’s effort to show both the children’s adventurous desires and Vojta’s guilty conscious, when he admits to destroying the helicopter and is ready to suffer the consequences, despite the pilot Heyduk having taken the blame.

A year after the release of Prázdniny v oblacích, Valášek teamed up again with screenwriter Ota Hofman for his next film Kouzelný den (A Magical Day, 1960). It tells the story of a young Honza, who, together with his classmates and older sister Eva, practice their gymnastics performance for the local round of the Spartakiad. He has to overcome a series of obstacles and resolve one problem to be able to take part in the special event with his older friends. In the film, Valášek playfully and poetically sketches the world of children and the big and small problems that they have to deal with in life. Contributing substantially to this are the performances of the child actors, headed by Jiří Lukeš. The final mass gymnastics event satisfied the requirements of the time, but it is all the more spectacular by the way it is performed by the young children.

As he did in the case of his feature film debut, Jan Valášek also looked to popular children’s literature to film his next feature film Malý Bobeš (Little Bobeš, 1961), which is based on Josefa Věromír Pleva’s book of the same name. The film captures the first part of the book, which describes the adventures of young Josef Janouš, nicknamed Bobeš, in his home village before the First World war. The pre-schooler gradually gets to know the world around him and makes his first friends. Valášek again cast Jiří Lukeš in the main role.

The film describes the village and society through a young child’s perspective. Youthful naivety comes into conflict with the clearly divided world of adults. Standing on one side is Bobeš’s friend Boženka, who is the daughter of the reeve Libra and whose mother forbids her to play with Bobeš because of his lower social standing; standing on the other are the children of the unemployed cotter Bezručka, who are living in poverty.

Bobeš’s family suddenly finds itself on par with Bezručka family. While working in the forest for Libra, a tree falls on Bobeš’s father Janouš and cripples him to the extent that he can no longer do his job. The reeve’s unwillingness to offer Janouš lighter work and his sole interest in purchasing Janouš’s land forces Janouš to move his family to the city, where there is a greater chance of finding work.

The film Malý Bobeš provided a poetic portrayal of life in a village, and through the eyes of a young boy, we see how the local society functions. Bobeš slowly gets to know the world around him and how the problems of the adults in his life affect him as well.

Valášek’s next film Malý Bobeš ve městě (Little Bobeš in Town, 1962) is a direct continuation of Malý Bobeš. The gloomy environment of the city periphery contrasts with the poetic portrayal of the village in the previous film. Bobeš, again played by Jiří Lukeš, has to get used to new and hitherto unknown things. Here the difference in the social standing of the inhabitants is even starker. Maruška, the daughter of an alcoholic, is ostracised by the other children at school, but Bobeš understands that what is important is what his classmate is like and not how poor her family is. When he buys her a ticket to the circus with his own money, their friendship is solidified.

The problems that Bobeš’s family has to deal with affects his life greatly and he has to deal with this as best he can by himself. The family is forced to move from the rented flat because they do not have enough money and Bobeš’s father is fired because his horses bolted through no fault of his own, and is then arrested for organising a strike in the factory.

From the press of the time, we learn that: “The importance of Malý Bobeš ve městě lies mainly in that it shows the direction children’s films should take: not to avoid important social issues.” [6] Positive reviews have to be attributed to its showing the formation of the labour movement, of which Bobeš’s father is a part. The entire situation is seen through the children’s perspective: that the father tried to help the workers and was punished for this, but justice wins out in the end and he is released, to the relief and joy of all. The naivety of the child hero thus overlaps with the naïve way in which the world is depicted.

As part of his body of work for children, Valášek brought to film Karel Jaromír Erben’s classic fairy tale Tři zlaté vlasy děda Vševěda (The Three Golden Hairs of Grandpa Know-All, 1963). Valášek tried to update and modernise his story about a collier’s son, Plaváček, who is foretold by his fairy godmothers that he will marry a princess. The distinctive stylisation by Ivo Houf dominate the story. The shots are full of darkish decorations and cumbersome structures, and the entire arrangement seems theatrical. Another no less important aspect is the portrayal of the king by Radovan Lukavský. Compared to the classical fairy-tale depiction of the king as a negative character who wishes to prevent the foretold marriage, the film makes the character much more tragic. Fate, which the king tries to thwart, stands at the forefront. Thus, the film creates a more three-dimensional character than appears in classical stories and their black-and-white portrayal of the world.

Valášek’s next project, the short film Když brečí muži (When Men Cry, 1964), brought Valášek and screenwriter Jan Procházka together. The more civil film tells the story of 11-year-old Olda [7], who has to be hospitalised after an accident on his bike. He tries to put on a brave face in front of the doctors and his mother, whom he does not want to worry even more. It is not until he is alone that he is given the space he needs to release his emotions and cry. When under the scrutiny of other’s, Olda tries not to show his emotions. In this film, Valášek tires to delve deeper into the psyche of a child.

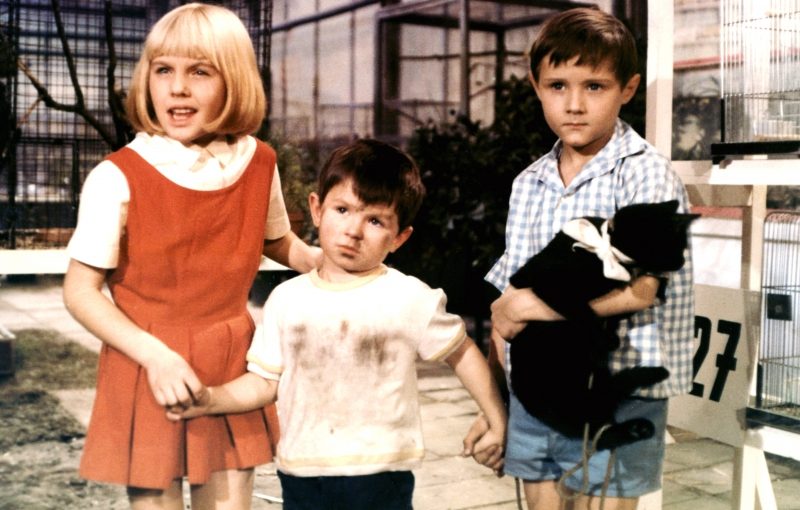

The sprightly comedy Když má svátek Dominika (Dominika’s Name Day, 1967) is built on a playful children’s story. Little Dominika meets Honza and his younger 4-year-old brother Míša, whom she gets in exchange for a stolen cat. The events take place one summer day, during which the children experience a lot of funny moments and find out all that can happen because of the mentioned exchange, which Honza and Misa’s parents are not happy about at all.

Based on a simple storyline, Valášek sets up a host of comical situations in the film, be it the security guard at the bird exhibition, Dominik’s and Honza’s efforts to wash dirty Míša or a group of detectives in disguise. Each event is accompanied by a musical number, where a group of guitar-strumming boys and dancing girls wander through a housing estate and the surroundings where the story takes place. The playfulness is also reflected in the use of various colour filters or in the way the shots are composed. Když má svátek Dominika is a playful film for children that depicts an idealised world in which everything turns out as it should to everyone’s satisfaction.

In his next film, Naše bláznivá rodina (Our Crazy Family, 1968), Valášek again works with screenwriter Jan Procházka. Unfortunately, this will be their last joint effort. During the final work on the film, the director died unexpectedly and the picture was completed by Karel Kachyňa.

The story of an eccentric, bespectacled family is told from the point of view of the 12-year-old daughter Jana. The parents’ strange behaviour after their return from the hospital makes her suspect that they want to get a divorce. She decides to find out if this is true and initiates her older sister Zuza into the plan. The siblings begin to fear that their familiar and safe microcosm will fall apart. During filming, Valášek stated that his goal was to make a film about “small things; about the worries and joys of a small but unformed and still dependent person chained with their big human heart to the world around them.” [8]

In the background of the main storyline there are many comical and funny situations experienced by the characters, which Jana comments on with wit and levity. The mother (Jiřina Jirásková), despite her poor driving abilities, never pays ticket to officers who are younger the 50; grandma (Jiřina Šejbalová) refuses to sit beside her daughter on the so-called seat of death; and this all is comically commented on by the father (Vladimír Menšík) with the words that they have no other kinds of seats in the car. Often Jana herself complicates the family situation just for fun and follows the chain of events she triggered, e.g. when she hides the tickets to the cinema.

The sweet, eccentric, three-generational family and their comical everyday situations are reminiscent of the series of films by Jaroslav Papoušek about the Homolka family. The only question that remains is to what extent did Karel Kachyňa influence the film and how much does the film fulfil the vision of the prematurely deceased director.

In his work, Jan Valášek focused mainly on the youngest viewers, about which he proclaimed: “It is above all necessary to want to understand children. I believe this is far more important than issuing various edicts about raising children, because only good works of art can awaken something inside a child.” [9] He tried to transfer their naïve and playful world and their desire for adventure to the screen, an effort in which he was more or less successful. Perhaps only because of his early death that his work is given somewhat less prominence that that of other filmmakers from the same period who also made films for children.

Notes:

[1] Jan Valášek was in fact four years older than Milan Vošmik, but began studying at FAMU later. Valášek and Václav Nývlte are the authors of the idea and screenplay for Vošmik’s 1960 psychological film Zlé pondělí (Tragic Monday).

[2] Hrbas, Jiří, Jan Valášek. Soustavná tvorba pro děti a mládež (Systematic Production for Children and Youth). Film a doba 19, 1973, Vol. 3, p. 126.

[3] Hrbas, Jiří, Jan Valášek. Soustavná tvorba pro děti a mládež (Systematic Production for Children and Youth). Film a doba 19, 1973, Vol 3., p. 127–128.

[4] Hrbas, Jiří, Jan Valášek. Soustavná tvorba pro děti a mládež (Systematic Production for Children and Youth). Film a doba 19, 1973, Vol. 3, p. 126.

[5] Vrabec, Vlastimil, Prázdniny v oblacích (Holiday in the Clouds). Film a doba 6, 1960, Vol. 7, p. 489.

[6] Soeldner, Ivan, Děti v kině a na plátně (Children in the Cinema and on the Screen). Film a doba 9, 1963, Vol. 6, p. 312.

[7] Screenwriter Ivo Pelant was cast in the main role.

[8] Hrbas, Jiří, Jan Valášek. Soustavná tvorba pro děti a mládež (Systematic Production for Children and Youth). Film a doba 19, 1973, Vol. 3, p. 132.

[9] Režisér Jan Valášek o filmu “Když má svátek Dominika” a o filmu pro děti vůbec (Director Jan Valášek about the film “Dominika’s Name Day” and about Children’s Film in General). Filmové informace 17, 1966, Vol. 47 (November 23), p. 1.