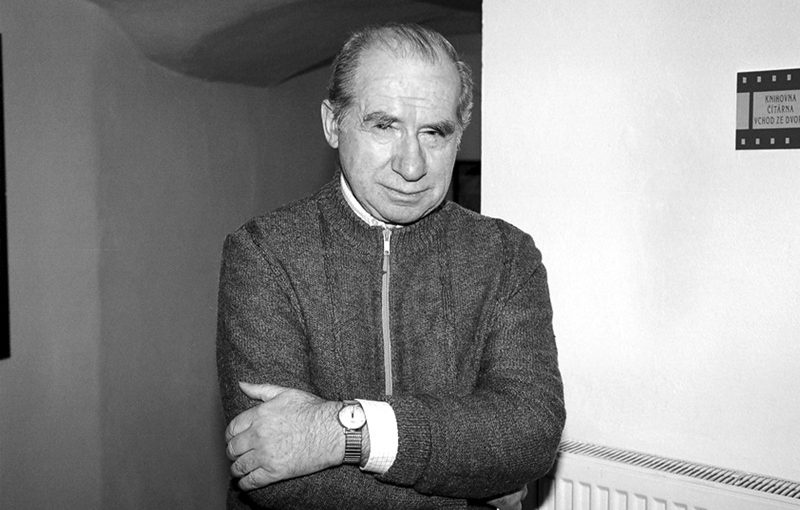

Jiří Gold was born on 17 January 1936 in Ostrava. He graduated from secondary school in Sušice (1954), and after attending a semester at the Railway University in Prague, he began studying scriptwriting at the Film Faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (FAMU) under M. V. Kratochvíl and A. F. Šulc (1955–1961). He published his first poems, which he indirectly categorized as contemporary everyday poetry, in Kultura magazine in 1957. During his studies, he contributed to the screenplay of Zdeněk Sirový’s film debut František Tichý (1958) and the screenplay of Bohuslav Musil’s Eso (Ace, 1961). After graduating from FAMU, he began working as a scriptwriter for the film production company Krátký film Praha, where he remained until 1991. In the 1960s, he worked on screenplays for films by Juraj Jakubisko [Déšť (Rain), 1965], Jan Švankmajer [Zahrada (The Garden), 1968] and Evald Schorm [Křepelky (Quails), 1969].

At the time, his first collections of poems – Nebe jasně zelené (Bright Green Heaven, 1964) and Minotaurus (The Minotaur, 1967) – were published. In them, Gold captures fleeting moments and images of war entrenched in his memories and carries on a dialog with antiquity. Frugal lyricism grows into epic compositions; descriptions of the everyday are constructed into narratives. Gold’s work also connects two aspects of modern Czech poetry: civilism and metaphysician abstraction.: “If we were to trace the author’s poetic pedigree, we would likely run across names such as Jiří Kolář, Jan Hanč and Vladimír Holan, i.e., authors for whom literature was either an ocular, enigmatic, prevaricating or intentionally incomplete testimony of existence; perhaps even an authentic Baudelaireian transposition of life experience into the realm of literature.” [1]

Tetralogy

In 1966, Jiří Gold directed the film Vidíš-li poutníka (If You See a Pilgrim), on which he built a trinity of similarly toned works. All are inspired by literature; nevertheless, they mature into a unique manner of expression through film. Vidíš-li poutníka, despite its free narrative, most approximates the portrait genre. In it, Gold combines three types of text pertaining to the poet Karel Hynek Mácha: the poet’s masterpiece Máj (May), critical responses to the poem at the time and the poet’s diary. Their merger results in a complete portrait of the poet set against a historical backdrop. By including free visual associations in the film, Gold creates less of a period film than unique artistic gesture. He then applies this principle in other parts of the tetralogy: “It’s about looking for the raw nerve of creation that responds sensitively to the period. We observe analogy, i.e., images that stand in for a reality that cannot be named directly.”[2]

With each new film, this poetic designation of reality grows stronger. According to Gold, Kulhavý poutník Josef Čapek (The Lame Pilgrim Josef Čapek) is already a “fictional biography” built on citations from Čapek’s books Lelio, Kulhavý poutník (The Lame Pilgrim) and Psáno do mraků (Written in the Clouds). No further commentaries are available, whereas the visual component layers various shots on top of one another to metaphorically develop Čapek’s fundamental themes of nothingness, nature, spirit and freedom. In the following film Zaklínání (The Incantation), the verbal accompaniment is limited to short excerpts of two works by František Halas: the litanic poem Nikde (Nowhere) and the lyrical prose Já se tam vrátím (I Will Go Back). The parallel alternation anchors the end poles of the poet’s imagination to the present: the tension between demise/death and chaos on the one hand, and home, order and life on the other. These aspects are also expressed in contrast with the narrations by Otomar Krejči and Jan Kačer. Kačer’s original recitation which was done in a whisper had to replaced with a normal timbre of voice at the request of Ústřední půjčovna filmů.

Gold attained the heights of poetic abstraction in the film Rafel mai amech izabi almi!, which was subject to even greater censorship. The name refers to the cry of Nimrod, the giant from the ninth circle of Dante’s Inferno. The literary source need not be further expanded upon, as the symbolism of the title is entirely clear: in the middle of the circle is a frozen lake in which the souls of political traitors suffer. Gold only works with an associative montage of shots made for the most part in a snow-covered dump, and a soundtrack comprising white noise, strings, synthesisers and collages from the press of the time. The message of the film is clear nevertheless. After its completion in 1969, negative modifications were made again, the spoken text was removed and it was renamed Smetiště (The Dump). The crippled version then only enjoyed limited distribution in film clubs. The author managed to retain a copy of the original, however, which he donated to the collections of the National Film Archive.

Normalisation

During Normalisation, Jiří Gold could neither director nor publish. Two of his completed screenplays were never filmed. His book of experimental poetry Kniha realit (Book of Realities) was rejected for publication. In it, Gold responded both to the literary directions of the time and to his films: “The more instalments of the tetralogy that were filmed, the more intensively did I try to create an equivalent to each film in the form of my own poetry. The last instalment – Rafel mai amech izabi almi! – should have been a direct merger of verbal, visual and aural expression. In the first phase of experimental texts, I tried to use newspaper cuttings, from which I made a collage and tried to capture the absurdity of the time in the poems created in this way. The second phase includes the finalisation of certain texts and laying them out into certain shapes as well as combinatorial texts where certain motifs repeat over and over. I worked most intensively on composing texts on the principle of dice: I chose fragments of words, divided them into six categories according to the colours of the dice and numbered them. I wrote down whatever it was I rolled.” [3] Jiří Gold wrote experimental poetry even in the 1970s. He was not able to publish any of the work until 1989, except in insignificant magazines. In the second half of the 1980s, Gold began to create dated rhyming records. These poetic diaries were later published in the collections Samospád samoty (The Gravity of Solitude, 1998) and Ze dna na den (From the Bottom to the Day, 2003).

Despite the ban on his works, Jiří Gold remained a scriptwriter at Krátký film, contributing to films by Rudolfa Krejčíka [Finská zima (The Finnish Winter), 1974], Petr Skala [Kameny (Stones), 1981] and Jan Špáta [Šumavské pastorale (Bohemian Forest Pastoral), 1975]. His collaboration with Václav Hapl was important: as a scriptwriter on Cena vítězství (The Price of Victory, 1972) and as a co-scriptwriter on Slunce (Sun, 1973) and Lesy umírají tiše (Forests Die Quietly, 1978). During Normalisation, Jiří Gold was also a sought-after commentator: he wrote commentaries for the films of Jan Němec [Mezi čtvrtou a pátou minutou (Between the Fourth and Fifth Minute), 1972], Bohuslav Musil (Viribus unitis, 1974), Karel Zeman [Čarodějův učeň (The Sorcerer’s Apprentice), 1977] and others.

Post-November Output

After the fall of the Communist regime, Jiří Gold was again allowed to direct films and publish books. His older verses from the 1980s and his contemporary work were included in the collections Noci dní (Nights of the Days, verses from 1991), Skvrny a dotyky (Stains and Strokes, verse from 1992), Sutě: písky: drtě (Debris: Sand: Rubble, verse from 1998) and, finally, …in vino scribere (version from the period 2000–2001). In them, Gold transposes direct diary records into more complicated forms. According to Radim Kopáč: “The poet more than ever before polemises about the classical understanding of a diary as an eye witness that responds directly to the impetuses of the time and places brightly lit quotidian ‘events’ before the reader. Although Gold’s poetry published after 1989 is based on facts, they mature into peculiar variations of philosophical queries and reflections that are entirely and definitely balanced with temporal and spatial determinacy.”[4]

Gold’s directorial work then developed the documentary portrait genre in particular – be it independently or in cooperation with other filmmakers (Vladimír Skalský, Petr Štěpánek and Petr Zrno). Between 1991 and 2003, Jiří Gold worked as a screenwriter for Czech Television, for whom he created dozens of film portraits about various personalities of Czech cultural life (writer Marie Kubátová, photographer Jiří Havel, artist Jan Koblasa and so on). Among the most distinctive films is Nevyhnutelnost Emila Juliše (The Inevitability of Emil Juliš). In it, Gold revisits certain techniques from the 1960s (expressive movements of the camera, tonal contrasts and montages of landscapes and works of art); pivotal, however, is the living author’s direct testimony. The film is a unique dialogue between two poets who are similar in their approach to their work (experimental poetry) and even share the same fate (not being allowed to publish during the height of their creative powers).

Footnotes:

[1] R. Kopáč, Mrtvá krajina žije nejzběsileji (A Dead Landscape Lives Most Frantically). Dobrá adresa, 2003, p. 8, p. 23.

[2] R. Kopáč, ibid., p. 25.

[3] R. Kopáč, ibid., p. 24.

[4] R. Kopáč, ibid., p. 26.